- 1Department of Neurosciences, Rehabilitation, Ophthalmology, Genetics, Maternal and Child Health, University of Genova, Savona, Italy

- 2Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Orthopaedics, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

- 3Department of Education Sciences, School of Social Sciences, University of Genova, Genova, Italy

- 4Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, AULSS9 Scaligera, G. Fracastoro Hospital, San Bonifacio, Verona, Italy

Introduction: Migraine is one of the top ten causes of disability worldwide. However, migraine is still underrated in society, and the quality of care for this disease is scant. Qualitative research allows for giving voice to people and understanding the impact of their disease through their experience of it. This study aims at synthesising the state of the art of qualitative studies focused on how people with migraine experience their life and pathology.

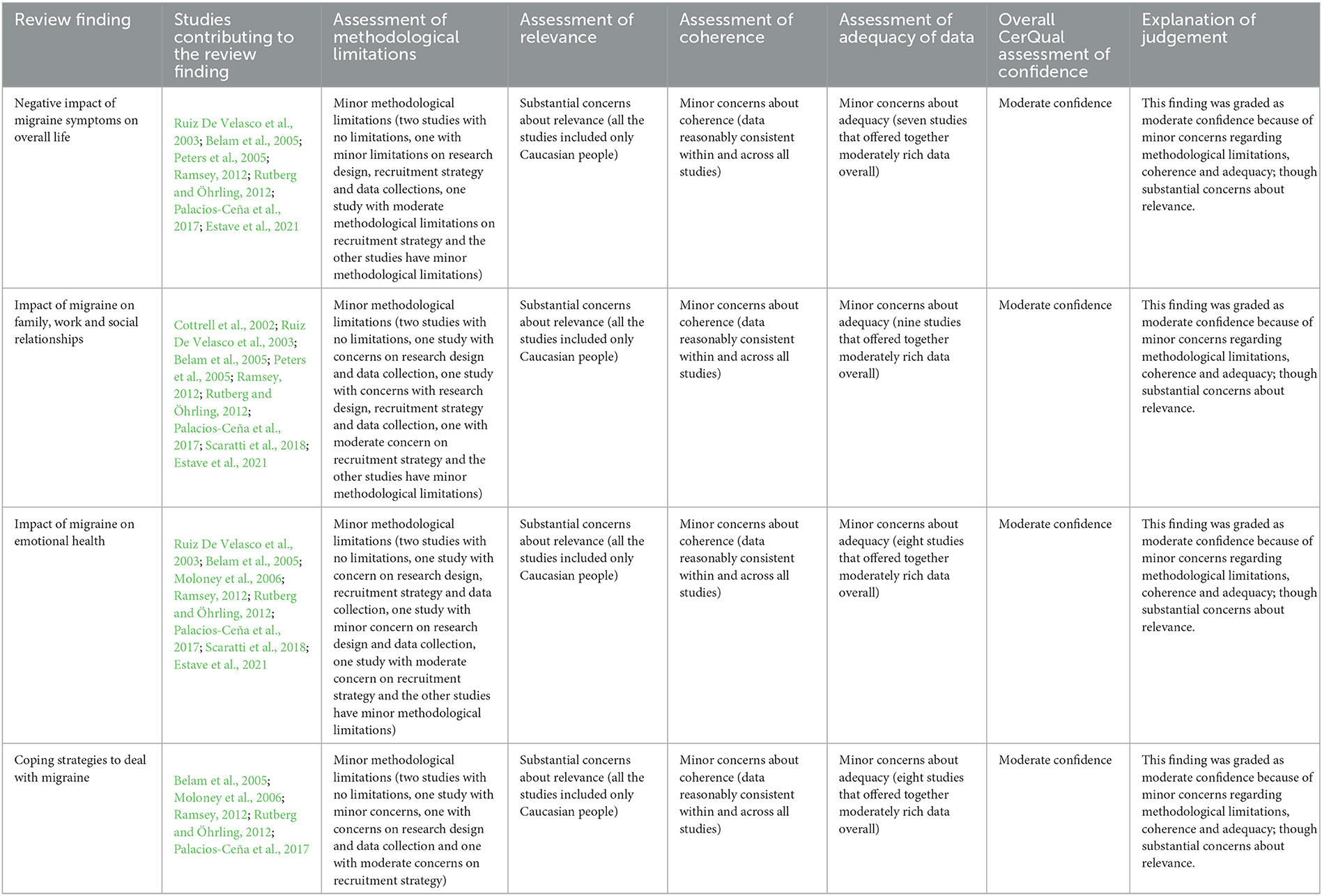

Methods: MEDLINE via PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Library were consulted up to November 2021 for qualitative studies. Studies to be eligible had to focus on adults (age > 18 years) with a diagnosis of primary episodic or chronic migraine following the International Classification of Headache. The quality of the study was analysed using the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) tool. The synthesis was done through a thematic analysis. CERQual (Confidence in Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research) approach was used to assess the confidence in retrieved evidence.

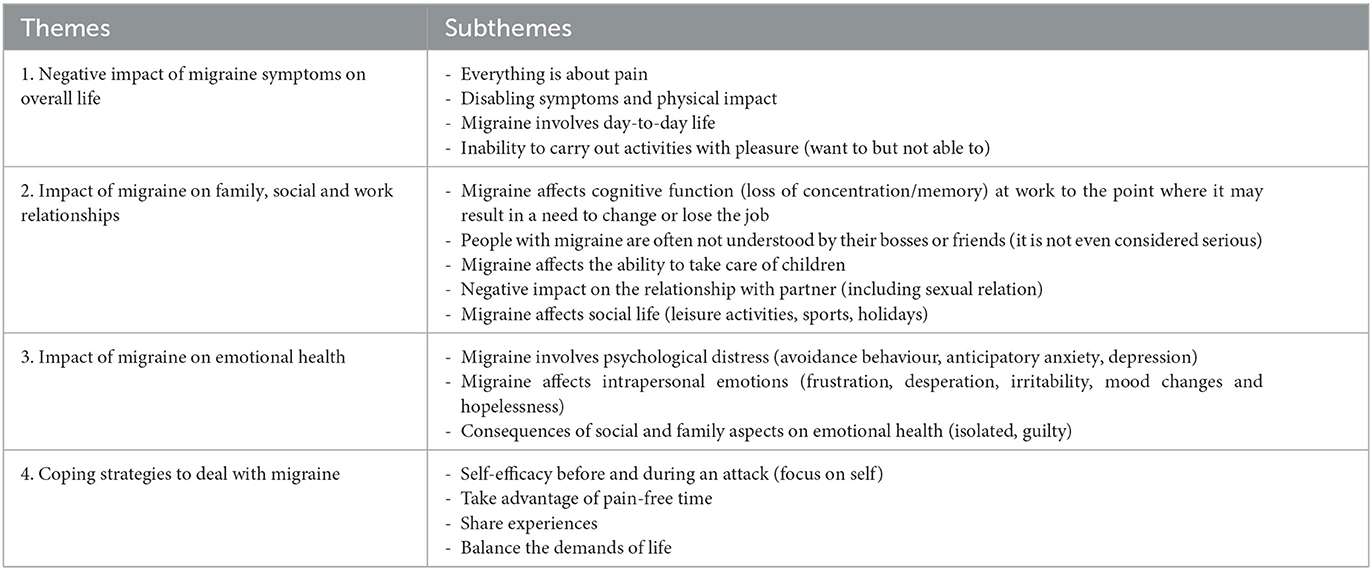

Results: Ten studies were included, counting 262 people with migraine. Our synthesis produced four main themes. (1) “Negative impact of migraine symptoms on overall life” as migraine negatively impacts people's whole life. (2) “Impact of migraine on family, work and social relationship” as migraine reduces the possibility to focus at work and interact with people. (3) “Impact of migraine on emotional health” as people with migraine experience psychological distress. (4) “Coping strategies to deal with migraine” such as keep on living one's own life, no matter the symptoms.

Conclusions: Migraine negatively impacts people's whole life, from private to social and work sphere. People with migraine feel stigmatised as others struggle with understanding their condition. Hence, it is necessary to improve awareness among society of this disabling condition, and the quality of care of these people, tackling this disease from a social and health-policy point of view.

1. Introduction

Migraine is a primary headache characterised by a throbbing pain on one side of the head, whose aetiology cannot be found in a specific structural alteration but in a combination of genetic and environmental factors (Burstein et al., 2015; Puledda et al., 2017). Migraine is the third most prevalent disorder worldwide and the second and third cause of disability and years of healthy life lost due to disability, respectively (Steiner et al., 2015, 2016, 2020). Moreover, it is one of the most common causes of absenteeism at work, and people with migraine experience a broad array of psychological distress due to their disease (Antonaci et al., 2011; Gandolfi et al., 2019; Donisi et al., 2020). Nevertheless, migraine is still underrated in society [World Health Organisation (WHO), 2011]. This underestimation of migraine disability is probably a result of a lack of education and knowledge of this disease among the general population and healthcare professionals [World Health Organisation (WHO), 2011; Guerrero et al., 2021; Pace et al., 2021].

The management of migraine is daunting as there is no definitive cure for this pathology, but symptoms-related management. People with migraine must learn how to coexist and cope with their disease. Recommendations for the treatment of acute migraine revolve around the importance of an early diagnosis and treatment, with the latter characterised by a personalised pharmacological intervention as first-line treatment (May and Schulte, 2016; Oskoui et al., 2019; Battista et al., 2021; Vanderpluym et al., 2021). Moreover, people with migraine should be educated on the lifestyle factors that can trigger or improve migraine attacks and the use of non-pharmacological treatments (e.g., muscular and relaxing techniques) (May and Schulte, 2016; Meyer et al., 2016; Falsiroli Maistrello et al., 2018; Garrigós-Pedrón et al., 2018). These treatments aim at reducing migraine frequency, duration and intensity. However, adherence to guidelines for the attack treatment of migraine is poor (Hepp et al., 2014; Olesen et al., 2022).

Considering the high impact of this disease, how underrated it is, and its difficult management, qualitative studies are needed to understand and give voice to people with migraine to understand their experience. By doing so, they allow for understanding people with different diseases, helping them in their therapeutic process, and improving their clinical management, influencing consultation behaviour and people's preferences (Peters et al., 2002; Noyes et al., 2018a). In 2002, Peters et al. stated that “few studies have been conducted on the patients' perspective on headache” (Peters et al., 2002). Since that moment, different qualitative studies have been published, leading to different systematic reviews. Nichols et al. analysed qualitative studies about the experience of different chronic headaches, including migraine (Nichols et al., 2017). However, migraine symptoms may overlap with other types of headaches, and chronic and episodic migraine might lead to different experiences worth exploring. Minen et al. conducted a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies on migraine management and patients' attitude to treatments and physicians (Minen et al., 2018). However, they did not take into account how people experience and live with this disease. In line with that, this study aims at filling the knowledge gap in the literature about people's perception of migraine (either episodic or chronic) and their implications on their life by synthetising qualitative studies on this topic.

2. Methods

A meta-synthesis is a systematic review and integration of findings from qualitative studies (Lachal et al., 2017). Meta-syntheses are concerned with understanding and describing key points, issues, and recurring themes within a research area of interest. Specifically, our meta-synthesis focuses on people's perception of a phenomenon (migraine) to offer different interpretations that might help the development of healthcare settings (Lachal et al., 2017). For this reason, the meta-synthesis approach suits the aim of this study, whose research question is: “How do people with migraine experience and manage their life?” The reporting of this meta-synthesis follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (PRISMA) 2020 (Page et al., 2021).

2.1. Eligibility criteria

2.1.1. Types of study

We included qualitative studies written in English and published in the last 21 years (2000–2021) that adopted different approaches (e.g., phenomenological analysis and grounded theory) and data collection methods (e.g., interviews and focus groups). Instead, we excluded studies in languages other than English that adopted quantitative designs such as systematic reviews, case reports, case series, and randomised-controlled trials (RCTs).

2.1.2. Participants

We considered eligible all the studies that included adults (age > 18 years) with a diagnosis of primary episodic or chronic migraine following the criteria of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD), with or without aura,1 excluding people with a headache not classified as primary migraine headaches. We did not impose any restrictions on the sex and gender of participants.

2.1.3. Types of evaluation

In this meta-synthesis, the focus is on people's experience of migraine. Thus, we included qualitative studies that focused on people with migraine. Instead, we excluded studies that concentrated only on caregivers or physicians.

2.2. Information sources

The research was conducted on MEDLINE via Pubmed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. Since there is no consensus about which databases should be used for meta-synthesis, we adopted the recommendations from the “Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews for Interventions” (Higgins et al., 2021). In their book, the Cochrane group suggested using MEDLINE via Pubmed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library as the bare minimum requirement and adopted other sources based on the specific topic of the review. Therefore, we also adopted CINAHL and PsycINFO as they are preeminent databases for qualitative and psychological primary studies. We consulted these databases up to November 2021.

2.3. Search strategy

The search strategy adopted is the SPIDER tool used for qualitative evidence synthesis: Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, and Research type (Cooke et al., 2012). The search strings used for all database is reported as Supplementary material 1. SB and AL conducted the search strategies with the help of a librarian from Lund University.

2.4. Selection process

Articles obtained from the research were uploaded to the Rayyan website after duplicate removal. Afterwards, two independent authors (AL and LFM) selected the studies applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria to titles and abstracts. In case of disagreement, a third author was consulted (SB). The full texts were read, and the final selection was decided through discussion by two authors (AL and SB). In addition to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, researchers evaluated the sample characteristics to include or not a study. The final purpose of this synthesis is to collect the experiences of a wide range of people with migraine, so if two studies had the same sample and similar settings, only one was included.

2.5. Data collection process

Two authors (AL and IC) independently extracted data from each study following the Cochrane indications (Noyes et al., 2018b) and using standardised Excel templates: author (year), title, country, setting, study design, objective, strengths and weaknesses, the total number of participants, sample characteristics, pathology of interest, frequency of migraine, and onset/years with migraine and disability rating scale. Then the two authors independently collected themes and subthemes from primary studies in a second Excel template. Disagreements in the data collection were resolved by either a consensus process or consultation with a third author (SB).

2.6. Methodological quality of the studies

Following Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Group's recommendations, the studies were assessed for critical appraisal with the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool by two authors independently (AL and IC) (Noyes et al., 2018b). CASP is the most common tool adopted for quality appraisal in health-related qualitative syntheses. The tool is made of ten questions that span from the use of appropriate methodology to the value of the results. Researchers can answer “yes”, “no”, or “can't tell” to each question. Each question has “comments” boxes to report why certain answers were given, and it is accompanied by suggested “hints” that help the researchers to reason upon the correct answer.

2.7. Data synthesis

A data-driven thematic analysis was used to synthesise the data with a descriptive approach (Dixon-Woods et al., 2005). Thematic analysis is a flexible method that identifies main or recurring themes from the included studies, summarising them under thematic headings. Specifically, data synthesis was divided into two phases. In the first one, two authors (AL and IC) thoroughly read the primary studies identifying their themes and subthemes independently. Then, they selected only those themes and subthemes that answered our research question, synthetising them based on their core meaning. In the second one, they discussed together their summarised themes and subthemes to reach a final consensus. In case of disagreement in the second phase, a third author (SB) was consulted.

2.8. Certainty of evidence

The Confidence in Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (CERQual) approach was used to assess the certainty of findings as either high, moderate, low or very low: it included the methodological limitations, relevance, coherence, and adequacy of data (Lewin et al., 2015). The methodological limitations of included studies were the result of the assessment made by the CASP tool. The relevance was the extent to which the setting or the inclusion criteria from the primary studies supporting review findings applied to the context specified in the review question (Lewin et al., 2015). The coherence assessed data consistency within and across all studies. The adequacy of data was an overall determination of the degree of richness and quantity of data supporting a review finding (Lewin et al., 2015).

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

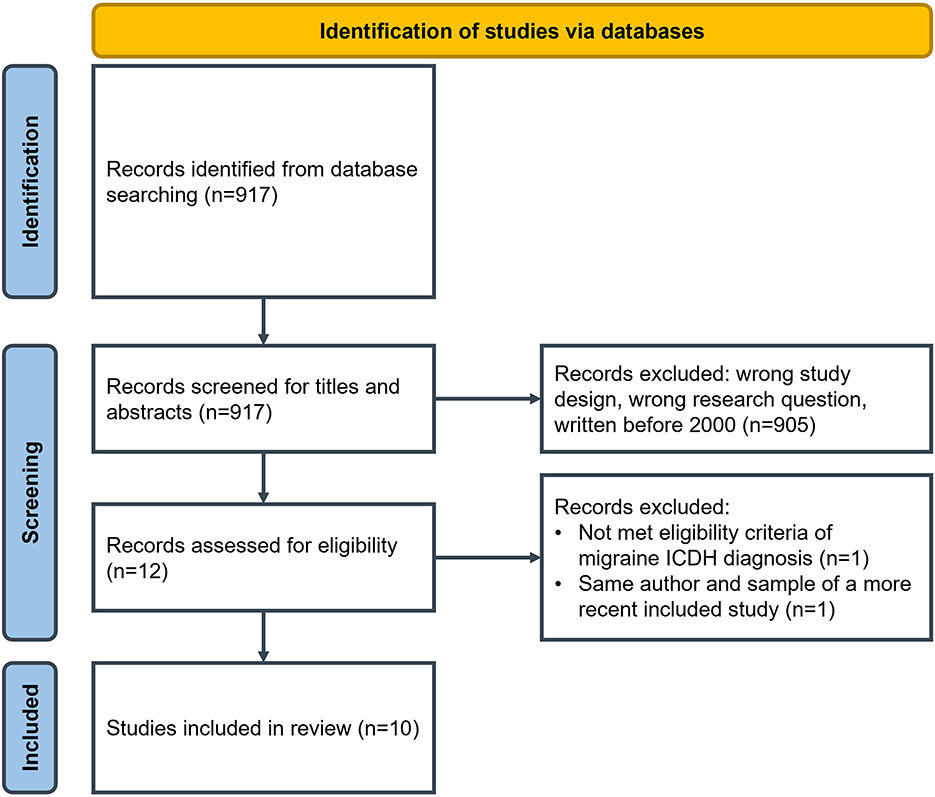

The research conducted on databases yielded 917 articles after the removal of duplicates. After the first screening selection of titles and abstracts, we excluded 905 studies. We read the full text of the remaining twelve articles. We excluded two studies as one did not declare a diagnosis of migraine following ICHD criteria (Leiper et al., 2006), and the other study (Moloney et al., 2004) presented the same sample (perimenopausal women) of a more recent study written by the same author included in this synthesis. Therefore, the final synthesis included ten articles (Cottrell et al., 2002; Ruiz De Velasco et al., 2003; Belam et al., 2005; Peters et al., 2005; Moloney et al., 2006; Ramsey, 2012; Rutberg and Öhrling, 2012; Palacios-Ceña et al., 2017; Scaratti et al., 2018; Estave et al., 2021) (Figure 1; PRISMA flow diagram).

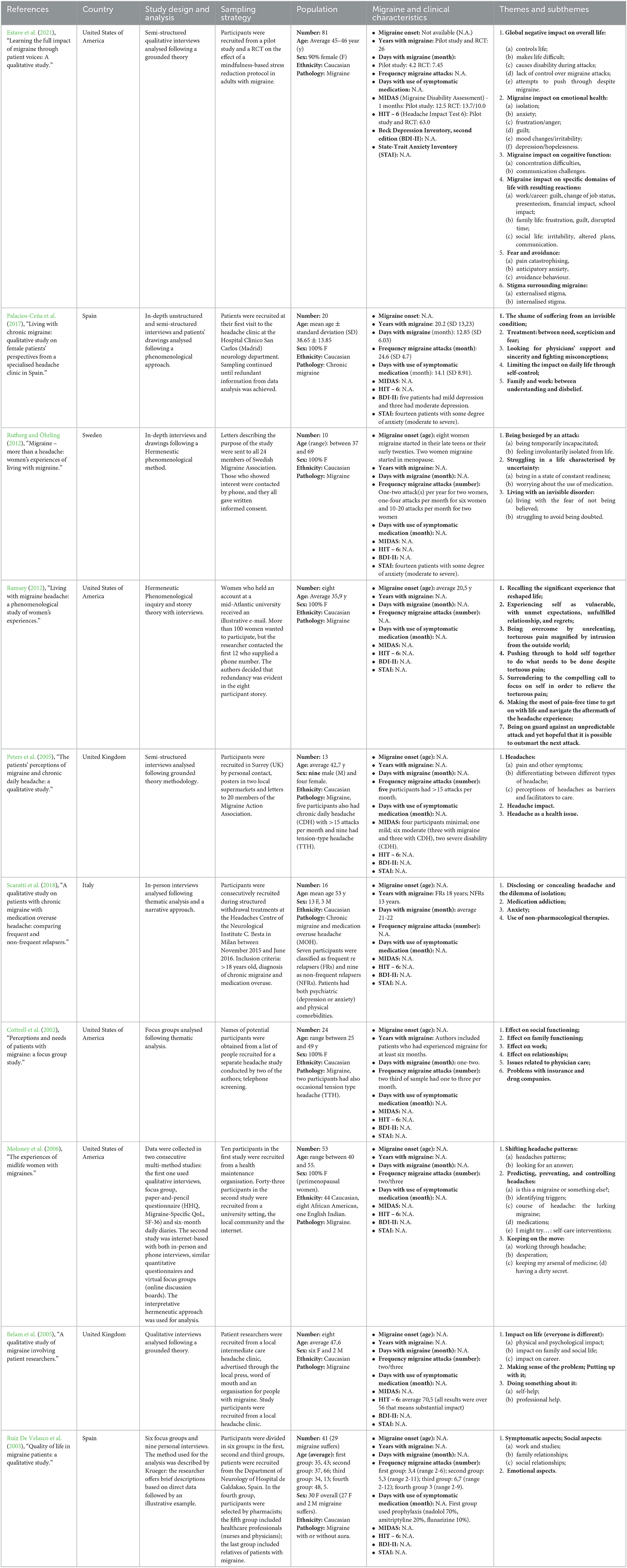

3.2. Study characteristics

The ten studies included in the research counted 262 participants with a diagnosis of migraine headache (either episodic or chronic) according to ICHD criteria. Table 1 includes all study characteristics and the different themes and subthemes extracted by the authors of the articles.

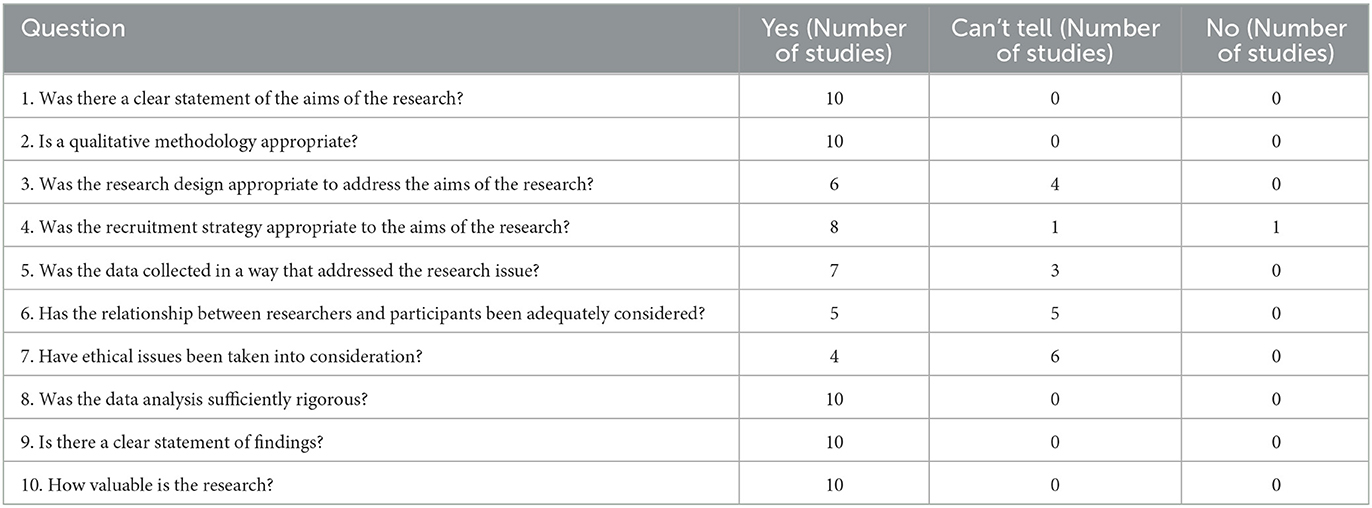

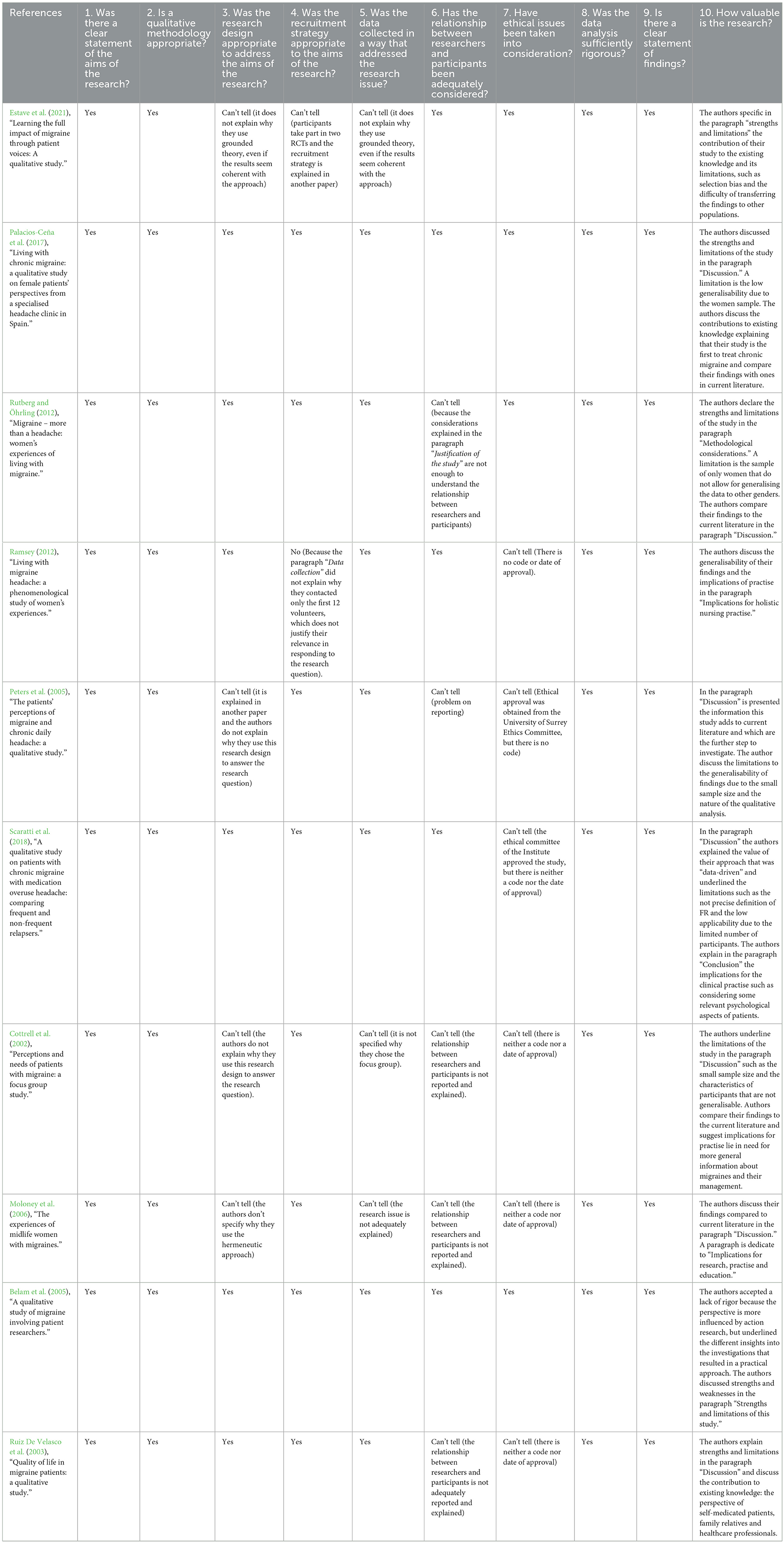

3.3. Methodological quality of the studies

The overall evaluations of CASP are collected in Table 2. The single answers with respective explanations for all the studies are reported in Table 3.

3.4. Results of the synthesis

The synthesis produced four main themes, as shown in Table 4. Every main theme was examined in some subthemes to explain more clearly the various life aspects affected by migraine.

3.4.1. Theme 1: Negative impact of migraine symptoms on overall life

The first theme was present in most studies (Ruiz De Velasco et al., 2003; Belam et al., 2005; Peters et al., 2005; Ramsey, 2012; Rutberg and Öhrling, 2012; Palacios-Ceña et al., 2017; Estave et al., 2021). It deals with how migraine affects patients' lives through physical symptoms, pain and the consequent inability to function at their best. This was the first theme that came to light because it explained how migraine negatively affected the lives of people with it and represented the underlying cause of the most negative experiences that emerged in the following subthemes.

3.4.1.1. Subtheme 1A: Everything is about pain

The participants described the pain as routine using a vivid range of metaphors to explain how impactful migraine was on them:

“A freight train coming through”, “A storm entering my head”, “As if my head would explode” (Ramsey, 2012).

“It's like somebody's put a knife through my head. The pain is so intense that for several seconds I don't even open my eyes, in the hope that I'm just dreaming about it” (Peters et al., 2005).

3.4.1.2. Subtheme 1B: Disabling symptoms and physical impact

Participants also experienced physical and disabling symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and visual or auditory impairment (aura). Aura did not affect all people with migraine, but it was considered one of the most disabling symptoms.

“Hearing that all day would kill me”, “A stereo that someone just keeps turning the volume up in my head”, “As echoing through my head”, “As fingernails on a chalkboard” (Ramsey, 2012).

“And your eyes begin to close because your whole body hurts and you feel pain when there is any kind of noise, light, anything at all” (Ruiz De Velasco et al., 2003).

3.4.1.3. Subtheme 1C: Migraine involves day-to-day life

People with migraine reported that their disease affected their life and hindered their ability to live it.

“I am losing a day of my life”, “Attacks make doing day-to-day things a lot more difficult. […] It makes day-to-day living harder” (Estave et al., 2021).

“You lose your life for a moment” (Rutberg and Öhrling, 2012).

3.4.1.4. Subtheme 1D: Inability to carry out activities with pleasure (want to but not able to)

Migraine symptoms also cause a loss of pleasure in daily activities.

“I have to stop doing things that I like to do, and I can't enjoy things I like to do”, “I never felt real joy because of always having this in the back of my mind” (Estave et al., 2021).

3.4.2. Theme 2: Impact of migraine on family, social, and work relationships

The second theme focused on how migraine affects people's relationships (Cottrell et al., 2002; Ruiz De Velasco et al., 2003; Belam et al., 2005; Peters et al., 2005; Ramsey, 2012; Rutberg and Öhrling, 2012; Palacios-Ceña et al., 2017; Scaratti et al., 2018; Estave et al., 2021). They explained how others considered them and how difficult it is to get along with social life. Participants voiced a problematic concept of not being understood by others, especially in the workplace where there could be consequences on their career up until the loss of their job. This problem sometimes emerged among friends and family. People with migraine perceived a certain sense of disbelief from others while they explained their situation as it is an “invisible condition”. The theme of failing to take care of children was recurrent in the studies (Cottrell et al., 2002; Belam et al., 2005; Ramsey, 2012; Estave et al., 2021). Moreover, a few participants expressed the negative impact on sexual relations voicing a common discomfort that was not often mentioned because of shame.

3.4.2.1. Subtheme 2A: Migraine affects cognitive function (loss of concentration/memory) at work and people feel they have to change their job or they even lose it

The participants complained about the effect of migraine on their work. This conception was recurring among the studies because migraine attacks also involved cognitive functions, and participants underlined the consequences of work.

“I've been fired from a job before because of my migraine attacks” (Estave et al., 2021).

“When I've got a migraine, I know that I can't give 100%, and that bothers me” (Ramsey, 2012).

“I try to look productive, but I'm only doing half” (Cottrell et al., 2002).

“It affects my career choice” (Belam et al., 2005).

“It's hard to concentrate”; “It affects memory” (Rutberg and Öhrling, 2012).

“There is this fear that if I get (a migraine) I'm gonna have to dive off (work), and I won't be able to fulfil duties” (Peters et al., 2005).

In most studies, participants voiced the theme of not being understood at work and its consequences on their work experiences.

“They thought it was a joke because nobody takes it seriously and nobody knows what migraine is”, “They've never had it they just think it's a headache, and it's not just a headache” (Estave et al., 2021).

“My workmate told my bosses that if I had a headache, I should take a pill and that it was no excuse not to go to work” (Palacios-Ceña et al., 2017).

3.4.2.2. Subtheme 2B: Migraine affects the ability to take care of children

Migraine often made childcare difficult, according to participants, who expressed it this way:

“I feel like I can't take care of him (18-month-old)” (Estave et al., 2021).

“It's very difficult to think that there are times when you can't take care of your child” (Ramsey, 2012).

“Mummy just can't deal with them [games] or do any housework or do anything” (Peters et al., 2005).

“I'm not the mom I wanted to be” (Cottrell et al., 2002).

“My son is only 11 and he has never known me any different” (Belam et al., 2005).

3.4.2.3. Subtheme 2C: Negative impact on the relationship with partner (including sexual relation)

The consequences of migraine attacks were also reported in the relationship with the partner, as the participants explained:

“It affects my husband because it puts more on him when I have one” (Estave et al., 2021).

“It's changing my life even in our sexual relations because since I began to have this pain, I haven't felt any kind of sexual arousal” (Ruiz De Velasco et al., 2003).

3.4.2.4. Subtheme 2D: Migraine affects social life (leisure activities, sports, holidays)

Participants' experience of migraine also involved social life.

“You can't lead a normal life, you can't go out dancing, to dinner, to the cinema. It changes the way you live.”, “It limits the time I can spend with my friends and even the desire to do sport” (Palacios-Ceña et al., 2017).

“Social life is affected a lot…I no longer have any relationship with them (friends)… the others, after a while, got tired of me” (Scaratti et al., 2018).

Moreover, participants reported their friends and acquaintances do not completely understand their situation. They struggle with legitimising it.

“I think people look like—yeah, right, everybody has headaches. They're not that bad, just get a grip and keep going” (Cottrell et al., 2002).

“The others don't understand because it is a sharp pain, and if you haven't experienced it, you can't imagine what it's like” (Ruiz De Velasco et al., 2003).

3.4.3. Theme 3: Impact of migraine on emotional health

The third theme dealt with emotional features that followed migraine and affected participants' lives even from a psychological aspect. Migraine involves psychological distress (avoidance behaviour, anticipatory anxiety, and depression). Psychological distress was common among participants, who suffered a lot and often presented themselves as overwhelmed by this condition (Ruiz De Velasco et al., 2003; Belam et al., 2005; Moloney et al., 2006; Ramsey, 2012; Rutberg and Öhrling, 2012; Palacios-Ceña et al., 2017; Scaratti et al., 2018; Estave et al., 2021).

3.4.3.1. Subtheme 3A: Migraine involves intrapersonal emotions (frustration, desperation, irritability, mood changes, depression, anxiety, and hopelessness)

Participants expressed their emotions, such as frustration and desperation, with condition that was difficult to explain and face. Emotions such as irritability and mood changes also affected the social relation triggering a vicious circle of discomfort.

“I'm more irritable and don't want to be around a lot of people” (Estave et al., 2021).

“Desperation is definitely part of the day” (Moloney et al., 2006).

“You are always in a bad mood, and besides” (Ruiz De Velasco et al., 2003).

“I get in such a bad mood that I can't stand anyone, you're irritable, you do not anyone talk to you, no-one to tell you anything” (Palacios-Ceña et al., 2017).

Among the different feelings, depression and anxiety were the most reported ones:

“[Attacks] cause a lot of anxiety because I don't know when I'm going to have one and I'm fearful. And when I have one, I'm fearful it's not going away” (Estave et al., 2021).

“I feel a little depressed. […] I can't react anymore, I'm tired of my headache” (Scaratti et al., 2018).

3.4.3.2. Subtheme 3B: Consequences of social and family aspects on emotional health (isolated, guilty)

Participants of Estave's study explained that physical and psychological symptoms led to feelings of isolation and guilty about time away from social engagement and family duties:

“I'm sorry it affects me because it takes me away from my family, my kids”, “My daughters, my husband and everybody … they just stopped including me in everything, so I felt like I was observing them live, but I wasn't really living” (Estave et al., 2021).

Participants of the studies by Palacios-Ceña et al. (2017) and Scaratti et al. (2018) explained the feeling of isolation:

“I am isolated from almost all of the people I know, except from my family of origin and from some friends…but I no longer have any relationship with them…the others, after a while, got tired of me” (Scaratti et al., 2018).

“It cuts you off from being with others; it separates you from everyone else” (Palacios-Ceña et al., 2017).

3.4.4. Theme 4: Coping strategies to deal with migraine

The last theme underlined the coping strategies that participants adopt to deal with their migraine. Participants voiced concern about the implications of migraine on every aspect of life, and, in most cases, it was hard to take on. However, they shared the strategies they adopted against the disability caused by attacks to cope with migraine.

3.4.4.1. Subtheme 4A: Self-efficacy as a support to manage migraine

Participants expressed their willingness not to be overwhelmed by pain. Therefore, they lived trying to go through the attack, managing it (Palacios-Ceña et al., 2017). They explained their will to keep on doing their activities, no matter the symptoms, to meet their expectations in a social or work context (Ramsey, 2012). However, they also showed to be aware of when taking care of themselves (Ramsey, 2012). Belam et al., in their study, talked about how people adopted self-help strategies to cope with attacks and look for remedies (Belam et al., 2005). The participants in Moloney et al. study added that it was essential to focus on causes and triggers to increase prediction and control (Moloney et al., 2006).

“You try not to let it affect you, to control everything, to deal with it, to be conscious of everything that might cause pain.” “I try to tolerate the pain as much as I can” (Palacios-Ceña et al., 2017).

“ […] you just have to go on through it” (Ramsey, 2012).

3.4.4.2. Subtheme 4B: Take advantage of pain-free time

Another strategy voiced by participants was using time devoid of pain to engage in activities like exercise and stress reduction to prevent other attacks and reduce the frequency.

“The good things are certainly that you don't have headache, but sometimes during the inactive phase you're actually getting over another one, and so you're trying to recoup, and sometimes redo things that you have done halfway […]. I try to take those inactive times to really enjoy life” (Ramsey, 2012).

3.4.4.3. Subtheme 4C: Share experiences

Participants voiced their need to share experiences, talk to others and explore meaning as they want to understand their condition and adjust it in the context of their lives.

“It was very helpful to be able to talk to and listen to other people who suffer from migraine”, “When you realise that other members of the family have migraine, you feel the battle is over—you understand why you get them” (Belam et al., 2005).

3.4.4.4. Subtheme 4D: Balance the demands of life

Living with migraine was a constantly evolving process that required constant attention and vigilance. This process included the ability to balance the demands of life.

“You learn to live with it, and you do not know what life would be without it, but it is like permanently wearing a backpack, which is though, you must always consider the possibility of not being able to do things” (Rutberg and Öhrling, 2012).

Participants voiced that they lived in a constant state of readiness to avoid triggers and control the attack. They described migraine with this metaphor:

“It's though that I am forced to live with somebody who always interrupts and decides what I should or should not do” (Rutberg and Öhrling, 2012).

3.5. Certainty of evidence

Table 5 reports the certainty of quality evidence (CerQual approach). None of the study findings was evaluated to be higher certainty because of weaknesses in relevance and minor methodology limitations of included studies. All the study findings were assessed as moderate confidence, which meant a good level of certainty because of minor concerns regarding the coherence and adequacy of data within and across all studies included.

4. Discussion

This is the first meta-synthesis that focuses exclusively on the life experiences of people with migraine (either episodic or chronic). From our synthesis, four main themes were brought to the forefront: “Negative impact of migraine symptoms on overall life”; “Impact of migraine on family, work and social relationships”; “Impact of migraine on emotional health”; and “Coping strategies to deal with migraine”. Our findings are in line with the ones from the meta-synthesis of Nichols et al. on chronic headaches (Nichols et al., 2017). People with chronic headaches from different genesis share a detrimental experience akin to the participants of the studies in our review. This shared experience stemmed from a similar sense of suffering, difficulties in Organising work and household chores, blaming one's own situation and other psychological distress such as anxiety. Our themes can also overlap with the ones retrieved from two qualitative studies on adolescents with migraine (Donovan et al., 2013; Walter, 2017), which were excluded from this meta-synthesis as we focused only on adults. Nevertheless, the experience of overwhelming pain and a sense of isolation caused by migraine are present regardless the age. However, the need to share experiences and social support is more evident among adolescents than in our sample (Donovan et al., 2013; Walter, 2017).

The first theme, “Negative impact of migraine symptoms on overall life”, showed that migraine symptoms are disabling and affect everyday life. This is in line with the current quantitative literature about the quality of life of people with migraine (Blumenfeld et al., 2011; Haywood et al., 2018; Buse et al., 2019). These studies suggest that people with migraine experience high levels of disability that impact their health-related quality of life. The qualitative data from this meta-synthesis delve into the quantitative ones, explaining where the disability has its greatest impact. For example, Estave et al. explained how people with migraine experienced doing things without pleasure or wanting to do something, but their disease hindered this attempt (Estave et al., 2021).

However, the most significant burden of people with migraine emerges in the work and social fields, as we explained in the second theme, “Impact of migraine on family, work and social relationship”. This theme focused on how people with migraine perceived their disease to impact different spheres of life, namely, family, work and social relationships. When it comes to family and work, people with migraine reported these spheres to be hindered by migraine attacks. This is in line with a study by Buse et al., where the authors reported migraine harmed people's careers and the feeling of being “good parents” in one-third of their population (Stewart et al., 2010; Buse et al., 2019). Thus, quantitative data underlines the prevalence of negative impact on jobs, whereas qualitative data sheds some light on where these problems are. In particular, people with migraine reported the loss of cognitive function (concentration and memory) while at work due to their symptoms. This sense of discomfort is further worsened by the lack of understanding from their bosses. When it comes to intimate relationships, Buse et al. underlined the difficulty of people with migraine in establishing and maintaining a relationship, ending up breaking up with their partner because of the recurrence of attacks that affect the ability to do things together (Buse et al., 2019). Ruiz De Velasco et al. highlighted that migraine could also impact the sexual sphere because of the pain of migraine attacks and its negative consequences on sexual arousal (Ruiz De Velasco et al., 2003). Problems in sexual spheres for these people can be underrated by a general sense of embarrassment, stigma and cultural taboo. People during focus groups felt embarrassed to talk about this topic, while they felt more at ease during individual interviews. Talking about sex is a challenge in healthcare (Brandenburg and Bitzer, 2009). However, for some people, sexuality is an essential yet complex phenomenon to feel ashamed about. This aspect must be taken into account during the care process for people with migraine to offer them multidisciplinary support that tackles this disease from different perspectives.

The third theme, “Impact of migraine on emotional health,” underlines the effects of migraine on emotional health. In the studies retrieved in our meta-synthesis, people with migraine reported a general sense of guilt. One participant stated, “It's my brain. It's my fault” (Estave et al., 2021). This sense of guilt was reported by other participants, and it is an overarching theme that was recently pointed out as one of the elements that contribute to the migraine burden (Estave et al., 2021). Rutberg and Moloney highlighted that participants' guilt might also stem from the lack of awareness and understanding of this disease in society (Moloney et al., 2006; Rutberg and Öhrling, 2012). As regards the issue of not being understood by others, which could lead to isolation, Estave explained that improving knowledge and awareness of migraine in the general public could reduce emotional disorders in people with migraine (Estave et al., 2021). These burdensome feelings can be one of the reasons behind the high prevalence of psychological distress among people with migraine. To previous evidence, 23.1% of people with migraine experience psychological distress (Korkmaz et al., 2019; Donisi et al., 2020). The study by Chu et al. found that the severity of depression and anxiety are related to migraine frequency and can alter the perception of pain (Chu et al., 2018). Therefore, it is fundamental to consider also the psychological sphere when taking charge of people with migraine.

The final theme dealt with the “Coping Strategies to deal with migraine” that people with migraine brought to the forefront to deal with their disease. These strategies included the importance of self-efficacy, taking advantage of pain-free time, sharing experiences and balancing the demands of life. Palacios Ceña et al. underlined that their study participants wanted to go and live through the attacks, managing them (Palacios-Ceña et al., 2017). Believing in the ability to produce specific performance attainments in their available capacity is called “self-efficacy” (Gandolfi et al., 2019; Donisi et al., 2020). High levels of self-efficacy were reported as a key factor in preventing attacks and adaptation to pain (Gandolfi et al., 2019; Donisi et al., 2020). However, as written by Ramsey et al., they can push people to deal with pain and also to meet their and others' expectations, levering external motivation (Ramsey, 2012). The participants from our studies were aware of the importance of adopting different strategies to manage their disease. Some of them were more symptoms-related, like taking medications, going to a cold dark room to eliminate all external stimuli and resting as much as needed (Ramsey, 2012). Other strategies were more part of a more systemic management of the disease, such as sharing experiences to understand their conditions, and seeking social support from healthcare professionals, other people with migraine, friends, relatives and acquaintances (Belam et al., 2005). The benefit of this need is also confirmed by quantitative studies where higher perceived social support was positively correlated with lower migraine intensity and psychological distress (Gandolfi et al., 2019; Donisi et al., 2020). Moreover, pain-free time is essential to reduce triggers and control migraine attacks. Ramsey and Moloney explained that some of their participants used their pain-free time to do exercise and stress reduction activities (Moloney et al., 2006; Ramsey, 2012). Thus, multimodal management should be considered where these and other adaptative coping strategies are offered and shared with patients to handle their symptoms once there, increase their levels of self-efficacy and take the most out of their pain-free time.

Several limitations of this study need to be addressed. This meta-synthesis has a sample made mostly of Caucasian people. The participants in our meta-synthesis came mainly from America and Europe. Moreover, most of the participants were women. However, this is in line with the worldwide prevalence of migraine, which is more common in women than men. We included both episodic and chronic migraine, which could be limiting in understanding the perception of these two types of migraine. Nevertheless, the meta-synthesis by Nichols et al. (2017) on chronic headaches underlined similar themes. Finally, our studies drew their results upon different theoretical under-pinning, ranging from interpretative phenomenological analysis to grounded theory. This is a common challenge in the synthesis of qualitative research (Rahimi et al., 2009). In line with that, we tried to adopt different strategies to be as rigorous as possible. First, we created a well and focused research question. Then, we selected the studies following specific criteria deemed as meaningful to answer our research question. Moreover, our research team was composed of different professionals (e.g., physiotherapists and psychologists) to take into account the particular aspects of the primary studies. Finally, the primary studies highlighted a shared experience of the disease by people with migraine, no matter the adopted approaches. The strengths of these studies are the rigorous and sensitive research we performed with the help of a librarian and the fact that we included only participants with migraine diagnoses (ICHD criteria). Moreover, we use the CerQual to assess the certainty of the evidence of our findings.

5. Conclusions

This study synthetised the available evidence on the experience of people with migraine. Several spheres of quality of life are jeopardised, namely, work, social life, and sexual and emotional health. People with migraine felt to be unseen and stigmatised at work and during their social life as others struggle with understanding their condition. There is a need to tackle this disease from a social and health-policy point of view by educating people with migraine and those around them about this condition, making this disease more “visible” to society.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Acknowledgements

This work was developed within the DINOGMI Department of Excellence framework of MIUR 2018-2022 (Legge 232 del 2016). The authors would like to thank the librarians from Lund University for their assistance in creating the search string for this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organisations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1129926/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The International Classification of Headache Disorders - ICHD-3. Available online at: https://ichd-3.org/ (accessed July 20, 2022).

References

Antonaci, F., Nappi, G., Galli, F., Manzoni, G. C., Calabresi, P., and Costa, A. (2011). Migraine and psychiatric comorbidity: a review of clinical findings. J. Headache Pain. 12, 115. doi: 10.1007/s10194-010-0282-4

Battista, S., Buzzatti, L., Gandolfi, M., Finocchi, C., Maistrello, L. F., Viceconti, A., et al. (2021). The use of botulinum toxin a as an adjunctive therapy in the management of chronic musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Toxins (Basel) 13, 640. doi: 10.3390/toxins13090640

Belam, J., Harris, G., Kernick, D., Kline, F., Lindley, K., McWatt, J., et al. (2005). A qualitative study of migraine involving patient researchers. Br. J. General Pract. 55, 87.

Blumenfeld, A. M., Varon, S. F., Wilcox, T. K., Buse, D. C., Kawata, A. K., Manack, A., et al. (2011). Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia 31, 301–315. doi: 10.1177/0333102410381145

Brandenburg, U., and Bitzer, J. (2009). The challenge of talking about sex: the importance of patient-physician interaction. Maturitas 63, 124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.03.019

Burstein, R., Noseda, R., and Borsook, D. (2015). Migraine: Multiple Processes, Complex Pathophysiology. J. Neurosci. 35, 6619. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0373-15.2015

Buse, D. C., Fanning, K. M., Reed, M. L., Murray, S., Dumas, P. K., Adams, A. M., et al. (2019). Life with migraine: effects on relationships, career, and finances from the chronic migraine epidemiology and outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache 59, 1286–1299. doi: 10.1111/head.13613

Chu, H., Liang, C. S., Lee, J. T., Yeh, T. C., Lee, M. S., Sung, Y. F., et al. (2018). Associations between depression/anxiety and headache frequency in migraineurs: a cross-sectional study. Headache 58, 407–415. doi: 10.1111/head.13215

Cooke, A., Smith, D., and Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 22, 1435–1443. doi: 10.1177/1049732312452938

Cottrell, C. K., Drew, J. B., Waller, S. E., Holroyd, K. A., Brose, J. A., and O'Donnell, F. J. (2002). Perceptions and needs of patients with migraine: a focus group study. J. Fam. Pract. 51, 142.

Dixon-Woods, M., Agarwal, S., Jones, D., Young, B., and Sutton, A. (2005). Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 10, 45–53. doi: 10.1177/135581960501000110

Donisi, V., Mazzi, M. A., Gandolfi, M., Deledda, G., Marchioretto, F., Battista, S., et al. (2020). Exploring emotional distress, psychological traits and attitudes in patients with chronic migraine undergoing onabotulinumtoxina prophylaxis versus withdrawal treatment. Toxins (Basel) 12, 577. doi: 10.3390/toxins12090577

Donovan, E., Mehringer, S., and Zeltzer, L. K. (2013). A qualitative analysis of adolescent, caregiver, and clinician perceptions of the impact of migraines on adolescents' social functioning. Pain Manag. Nurs. 14, 02. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2011.09.002

Estave, P. M., Beeghly, S., Anderson, R., Margol, C., Shakir, M., George, G., et al. (2021). Learning the full impact of migraine through patient voices: A qualitative study. Headache: J. Head Face Pain. 61, 1004–1020. doi: 10.1111/head.14151

Falsiroli Maistrello, L., Geri, T., Gianola, S., Zaninetti, M., and Testa, M. (2018). Effectiveness of trigger point manual treatment on the frequency, intensity, and duration of attacks in primary headaches: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Neurol. 9, 254. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00254

Gandolfi, M., Donisi, V., Marchioretto, F., Battista, S., Smania, N., and del Piccolo, L. (2019). A prospective observational cohort study on pharmacological habitus, headache-related disability and psychological profile in patients with chronic migraine undergoing onabotulinumtoxina prophylactic treatment. Toxins (Basel) 11, 504. doi: 10.3390/toxins11090504

Garrigós-Pedrón, M., la Touche, R., Navarro-Desentre, P., Gracia-Naya, M., and Segura-Ort,í, E. (2018). Effects of a physical therapy protocol in patients with chronic migraine and temporomandibular disorders: a randomized, single-blinded, clinical trial. J. Oral. Facial Pain Heada. 32, 137–150. doi: 10.11607/ofph.1912

Guerrero, A. L., Negro, A., Ryvlin, P., Skorobogatykh, K., Sanchez-De La Rosa, R., Israel-Willner, H., et al. (2021). Need of guidance in disabling and chronic migraine identification in the primary care setting, results from the european My Life anamnesis survey. BMC Fam. Pract. 22, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12875-021-01402-2

Haywood, K. L., Mars, T. S., Potter, R., Patel, S., Matharu, M., and Underwood, M. (2018). Assessing the impact of headaches and the outcomes of treatment: A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Cephalalgia 38, 1374–1386. doi: 10.1177/0333102417731348

Hepp, Z., Bloudek, L. M., and Varon, S. F. (2014). Systematic review of migraine prophylaxis adherence and persistence. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 20, 22–33. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.1.22

Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., et al. (2021). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2. Cochrane. Available online at: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed June 30, 2021).

Korkmaz, S., Kazgan, A., Korucu, T., Gönen, M., Yilmaz, M. Z., and Atmaca, M. (2019). Psychiatric symptoms in migraine patients and their attitudes towards psychological support on stigmatization. J. Clin. Neurosci. 62, 180–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2018.11.035

Lachal, J., Revah-Levy, A., Orri, M., and Moro, M. R. (2017). Metasynthesis: An original method to synthesize qualitative literature in psychiatry. Front. Psychiatry 8, 269. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00269

Leiper, D. A., Elliott, A. M., and Hannaford, P. C. (2006). Experiences and perceptions of people with headache: A qualitative study. BMC Fam. Pract. 7, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-27

Lewin, S., Glenton, C., Munthe-Kaas, H., Carlsen, B., Colvin, C. J., Gülmezoglu, M., et al. (2015). Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: an approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Med. 12, 1895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001895

May, A., and Schulte, L. H. (2016). Chronic migraine: risk factors, mechanisms and treatment. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 12, 455–464. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.93

Meyer, B., Keller, A., Wöhlbier, H. G., Overath, C. H., Müller, B., and Kropp, P. (2016). Progressive muscle relaxation reduces migraine frequency and normalizes amplitudes of contingent negative variation (CNV). J. Heada. Pain 17, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0630-0

Minen, M. T., Anglin, C., Boubour, A., Squires, A., and Herrmann, L. (2018). Meta-synthesis on migraine management. Headache 58, 22–44. doi: 10.1111/head.13212

Moloney, M. F., Strickland, O., Dietrich, A., and Myerburg, S. (2004). Online data collection in women's health research: a study of perimenopausal women with migraines. NWSA J. 16, 70–92. doi: 10.2979/NWS.2004.16.3.70

Moloney, M. F., Strickland, O. L., DeRossett, S. E., Melby, M. K., and Dietrich, A. S. (2006). The experiences of midlife women with migraines. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 38, 278–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00114.x

Nichols, V. P., Ellard, D. R., Griffiths, F. E., Kamal, A., Underwood, M., and Taylor, S. J. C. (2017). The lived experience of chronic headache: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative literature. BMJ Open 7, e019929. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019929

Noyes, J., Booth, A., Cargo, M., Flemming, K., Garside, R., Hannes, K., et al. (2018a). Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series-paper 1: introduction. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 97, 35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.09.025

Noyes, J., Booth, A., Flemming, K., Garside, R., Harden, A., Lewin, S., et al. (2018b). Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series-paper 3: methods for assessing methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in synthesized qualitative findings. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 97, 49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.06.020

Olesen, A., Schytz, H. W., Ostrowski, S. R., Topholm, M., Nielsen, K., Erikstrup, C., et al. (2022). Low adherence to the guideline for the acute treatment of migraine. Sci. Rep. 12, 8487. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-12545-2

Oskoui, M., Pringsheim, T., Holler-Managan, Y., Potrebic, S., Billinghurst, L., Gloss, D., et al. (2019). Practise guideline update summary: Acute treatment of migraine in children and adolescents: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Headache 59, 1158–1173. doi: 10.1111/head.13628

Pace, A., Orr, S. L., Rosen, N. L., Safdieh, J. E., Cruz, G. B., and Sprouse-Blum, A. S. (2021). The current state of headache medicine education in the United States and Canada: An observational, survey-based study of neurology clerkship directors and curriculum deans. Headache 61, 854–862. doi: 10.1111/head.14134

Page, M. J., Mckenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 88, 105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

Palacios-Ceña, D., Neira-Martín, B., Silva-Hernández, L., Mayo-Canalejo, D., Florencio, L. L., Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C., et al. (2017). Living with chronic migraine: a qualitative study on female patients' perspectives from a specialised headache clinic in Spain. BMJ Open 7, e017851. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017851

Peters, M., Abu-Saad, H. H., Vydelingum, V., and Murphy, M. (2002). Research into headache: the contribution of qualitative methods. Headache 42, 1051–1059. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02238.x

Peters, M., Huijer Abu-Saad, H., Vydelingum, V., Dowson, A., and Murphy, M. (2005). The patients' perceptions of migraine and chronic daily headache: A qualitative study. J. Heada. Pain 6, 40–47. doi: 10.1007/s10194-005-0144-7

Puledda, F., Messina, R., and Goadsby, P. J. (2017). An update on migraine: current understanding and future directions. J. Neurol. 264, 2031–2039. doi: 10.1007/s00415-017-8434-y

Rahimi, B., Vimarlund, V., and Timpka, T. (2009). Health information system implementation: a qualitative meta-analysis. J. Med. Syst. 33, 359–368. doi: 10.1007/s10916-008-9198-9

Ramsey, A. R. (2012). Living with migraine headache: a phenomenological study of women's experiences. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 26, 297–307. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0b013e31826f5029

Ruiz De Velasco, I., González, N., Etxeberria, Y., and Garcia-Monco, J. C. (2003). Quality of life in migraine patients: A qualitative study. Cephalalgia 23, 892–900. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00599.x

Rutberg, S., and Öhrling, K. (2012). Migraine–more than a headache: women's experiences of living with migraine. Disabil. Rehabil. 34, 329–336. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.607211

Scaratti, C., Covelli, V., Guastafierro, E., Leonardi, M., Grazzi, L., Rizzoli, P. B., et al. (2018). A qualitative study on patients with chronic migraine with medication overuse headache: comparing frequent and non-frequent relapsers. Headache 58, 1373–1388. doi: 10.1111/head.13385

Steiner, T. J., Birbeck, G. L., Jensen, R. H., Katsarava, Z., Stovner, L. J., and Martelletti, P. (2015). Headache disorders are third cause of disability worldwide. J. Heada. Pain 16, 1–3. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0544-2

Steiner, T. J., Stovner, L. J., Jensen, R., Uluduz, D., and Katsarava, Z. (2020). Migraine remains second among the world's causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J. Heada. Pain 21, 1–4. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01208-0

Steiner, T. J., Stovner, L. J., and Vos, T. (2016). GBD 2015: migraine is the third cause of disability in under 50s. J Heada. Pain 17, 1–4. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0699-5

Stewart, W. F., Wood, G. C., Manack, A., Varon, S. F., Buse, D. C., and Lipton, R. B. (2010). Employment and work impact of chronic migraine and episodic migraine. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 52, 8–14. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181c1dc56

Vanderpluym, J. H., Halker Singh, R. B., Urtecho, M., Morrow, A. S., Nayfeh, T., Torres Roldan, V. D., et al. (2021). Acute treatments for episodic migraine in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 325, 2357–2369. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7939

Walter, S. M. (2017). The Experience of Adolescents Living With Headache. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 31, 280–289. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000224

World Health Organisation (WHO) (2011). Atlas of Headache Disorders and Resources in the World 2011. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data, 3–23. Available online at: www.who.int (accessed July 20, 2022).

Keywords: headache, quality of life, disease management, patient participation, decision making, rehabilitation

Citation: Battista S, Lazzaretti A, Coppola I, Falsiroli Maistrello L, Rania N and Testa M (2023) Living with migraine: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Front. Psychol. 14:1129926. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1129926

Received: 22 December 2022; Accepted: 02 March 2023;

Published: 28 March 2023.

Edited by:

Changiz Mohiyeddini, Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, United StatesReviewed by:

Snehal Samal, Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Science, IndiaAynur Özge, Mersin University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2023 Battista, Lazzaretti, Coppola, Falsiroli Maistrello, Rania and Testa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marco Testa, bWFyY28udGVzdGFAdW5pZ2UuaXQ=

Simone Battista

Simone Battista Arianna Lazzaretti1

Arianna Lazzaretti1 Luca Falsiroli Maistrello

Luca Falsiroli Maistrello Nadia Rania

Nadia Rania Marco Testa

Marco Testa